message 21: facts and fictions

Hey there.

Well, look at you. It’s been a minute. I hope you’re well. This one’s long. (You may just want to click on the title so it sends you to the full post—your call.)

Some of this has been in my head for ages, but it largely started swirling together a month ago. I had a birthday, and I’m usually in a spooky headspace around that time. (A Leo who isn’t throwing a lavish birthday party and spoiling their guests is probably spending their big night conjuring knowledge on the moment of their own death; either way, there’s a lot of intense staring into a mirror, often with the aid of booze.) The mixed media towards the end speaks to that.

More importantly, I realized several key moments in my life had reached their five-year anniversaries: finishing my doctorate, getting married, moving to Texas, and everything in the poetry essay below. Actually, it’s more intense than that: they all happened within six weeks of one another, a genuine personal sea change. I hope that comes through.

I feel something stirring again—it’s a bit of the dog-ear sense one gets living through enough hurricanes. It’s neither foreboding nor glassy-eyed: I just feel as if something is afoot. Maybe eventually you’ll get to read about it.

I hope you like it. The next one will probably be all video and slime.

—KJ

facts and fictions

1

I didn’t realize you had died until two years after the fact. That’s nearly a criminal admission these days even for those furthest from our orbits: the grade-school classmate with cystic fibrosis, an unrequited hometown crush, a neighbor only known through waves and nods. Shame still sits on my neck from learning, much later, that Allison didn’t make it too far past her bat mitzvah, that Robert was killed during a tour of duty, that an old friend’s older husband succumbed to a heart attack he was still too young to have. Death hurts us not only with the pain of loss, but in the horror of learning our grief comes as an echo: a delay that wounds the wailer and the wall. News is news, but fact doesn’t remain in suspension: you are dying; you have died; you are dead; you have been dead. You been dead. You are dead-dead. Does grief grow stale? Can it become flat like a forgotten soda? Do my condolences begin to taste as weird as the expired food you’d bring over? Why do the words “I’m so sorry for your loss” feel tinned when I say them to myself in the mirror, over and over, metallic like your voice in the answering machine messages you’d leave my mother every afternoon?

2

I’m not the only one: my mother, your daughter, had been kept from your death for the same amount of time. I found out the same day she did, albeit at work and filtered through a Facebook Messenger chat littered with heart emoji and sad cartoon animals. The fluorescent glow of the labor union office gave me a migraine, but that was already a weekly occurrence. I think you always worked under the table.

You’re not the only one: my grandfather--the man you divorced fifty years earlier after firing his cop’s gun at him—had also croaked two years before I found out. But that was straightforward: the probate lawyer called my mother. Another emoji chat, another migraine. A drunk neighbor had already ruined the one thing of his I had, a champagne PT Cruiser he gave me when he moved from Miami Beach to a psychic community.

I’m not the one: I hadn’t seen you in over fifteen years. I gave a speech to my graduating class, you sat in the audience and bought me a burger and coke after, and I got the hell out of Hollywood, Florida two months later because I was both too smart and too stupid to pass up state school money. Your hair was still a tight blond perm, your Crown Vic was powder blue. I have no idea when they took away your driver’s license or peroxide.

You’re not the one: My mother never knew her grandmother, your mother, was still alive somewhere in Florida until the year I was born. I never knew her name. I still don’t. Whenever we had a family tree assignment in school, I knew the answers were always kind of made up: a green-eyed child named “Keegan” can fake most of it, especially one with very high test scores. But what was her name? What was it? And what was your final one?

3

The phrase “after the fact” carries so much—too much. First is the idea of fact. Fact, or rather “fact,” is in itself historical. The series of events that we understand as fact, the disparate series of observable instances that we consider true and bind as a discrete unit—and the weight that it holds distinct from opinion or gossip or rumor or conjecture—all of that has a past. News is news, but at some point, news was itself news. (Fact, facts; new, news; sorrow, sorrows.)

Even history has a history: not all facts are treated equally. The historian can control only so many of their biases. The archive can contain only so many papers. The laws can save only so many documents from the shitter or shredder. The storyteller can recite the generations-long epic to his apprentice only so many times before giving in and letting him do sixteen bars. The fires can be held back only so many times. (Linear A made complete sense only so many times.)

Even fact has a present: Are we talking about legal burdens of proof or the scientific method? Are we talking about speech or deed? The pragmatic illusions that transform a people into a nation or the collective delusion of white nationalists? Induction or deduction? The bulldozer of imperial bureaucratic documents or the resistance built in reading against the grain and outside of the state? The pluperfect or the conditional? Bayes or shadowy caves? (Yes, if; no, but.)

My facts have a present: “I drank an overpriced beer while I drafted this section.” “I don’t know your mother’s name.” “You never knew that I moved to Texas.” “I drank another overpriced beer revising this section.” “You always kept your bomber jacket hanging in the back of your Crown Vic.” “I don’t know if you were buried or turned to ash.” “I don’t know what you owed that couldn’t be paid in flame and teeth.” (Ash, ashes; tooth, teeth; sorrow, sorrow.)

4

Questions and answers are both territory of the living. I spent a decade practicing as a historian, a faith solely built around the obsession of asking: “Well why? Why? Why? How? Why?” so one can tell stories to eager believers chanting “And then what? And then what? And then what? And then what?”

It’s quantum obsessive compulsive agnosticism: there is no way to be certain of anything whatsoever, but one is also the god of the story. In this way, that’s the truest source of power: we’re all deities of our own making. This must have pissed off the actual gods at first. Clio didn’t create all of that archive dust for nothing. She probably conjured up counterfactuals out of spite.

Your granddaughter, my cousin, used to conjure spirits on a Ouija board, in between doing sets of acrylics. It’s pretty hard to ask And then what? And then what? on a planchette in a carport.

I convinced myself that I was still a historian in order to find some instance of you online. I don’t have anything of yours, not a single goddamned thing—not your booster seat height nor your old land boat car nor your Costco card nor your fondness for chemical pesticides. All I have, seared into my head, is a single photo of you in my parents’ wedding album, amid the family interstitial: one aunt looking like a Floridian Glenn Close, my grandfather a vampire who became a blanched salesman, you a freshly permed terrier eager for ankle blood.

I imagine a mound of dirt or a mantle-top urn: But what was your actual name? I know the nickname on your bomber jacket hanging off the rear passenger hook, which my brother and I would joke about outside of the Crown Vic, outside the reach of a front row arm. I’m digging at the heap of letters like a starving fox. I knew your grandma name was different than the one our cousins used. Clio has transferred my call to Mneme. I know all the names they called you behind your back, but I don’t know anything else. I’ve prayed to Apollo’s women, I’ve prayed to Herodotus and DuBois, I’ve prayed to myself: What was your full goddamn name?

I can spell still even if you refuse to sit by the letterboard. It’s easier to conjure you that way, fingernails ragged on the plastic: f – o – x – y. Street names are still names, probably more so.

5

The body is a first-order archive: Every inch of your hoarder spaces had been stewed in moth balls. You threw them in every corner, under the sinks, in the crevices and cracks of your homes. It was like magnified cat piss, only worse because you had no cats. The acid tree stink stuck to our hair, our teeth, the bags of bags, the rotting food in the back of the fridge, cream cheese from some bygone presidential administration. The stench moved from the condo you never seemed to pay for to the trailer you definitely never paid for. The taste defied physics, seeped through plastic wrappers, turned the cookies you gave to us uncannily soft and acrid with chemical leeching. it was too hot in Miami for you to even ever own wool.

The brain is a second-order archive: When my mother was a girl a neighbor dog would come and try to attack her day after day. One day it finally bit her terribly, leaving her bloodied. Three days later, the dog lay rot dead in its yard, drowned in its own sick.

6

I don’t see you in my dreams. I’m not a cynic: I write poems, for fuck’s sake. I’ve seen myself 25 years from now; I’ve seen myself 25 years ago. I’ve seen every family member but you. It’s why I’ve imagined you into being here, your blond perm, your tattooed scowl, your endless trail of racial slurs. What remains uncertain is whether you’re roaming the earth, stuck until someone does enough penance on your behalf, or whether you went straight to hell. I’m certain you have a soul—I can’t fully escape a Catholic youth you had no say in—but I don’t know what you’ve done to it.

If you showed up in my dreams, in between the drool and teeth gnashing, finding your way through the recurring car crashes and bathhouses, all I could do is ask you, over and over: where did you go? We may leave with our souls but I don’t think we keep our ears, our tongues slack with the siren calls that survive our sense of how to shape our lips or even the words themselves. You could come to me as an elk, a golden bowl—you could come to me in a parted cloud or a gurgling toilet, lights flickering and lightbulbs shattering. You could come to me as the answering machine drone you’d leave one, two, three times a day for a decade straight:

judithitsyourmotherpickupthephone

judtihitsyourmotherpickupthephone

judithitsyourmotherpickupthephone

judithitsyourmotherpickupthephone

judithitsyourmotherpickupthephone

You could visit me every night, when I have no choice but to see you, you could come to me when I’m ten years old again and I could do is ask your drooling ghost where did you go?

7

You exist in three traces:

I see you once as a census line, a seventeen-year-old girl in Miami living with your sister. I see you again months later, ready to graduate high school in 1951. It’s unclear whether you’re already pregnant with my aunt by then, but the yearbook makes clear that you’re a member of two singing clubs and an anti-drinking league. It’s the only time I’ve seen you young, or thought of you without a carburetor voice and bartender’s hands. I see you one final time, in a divorce notice from the early seventies. My grandfather would finally sign the papers in order to marry his second wife ten days later.

You exist in three traces behind a paywall.

After I find you for a ransom, I want more. I want to find your death notice. I convince myself that enough creative googling will lead me to the one wrinkle of the Internet I had somehow avoided. I used to play this game with my dissertation, but since my career as a historian is also dead I have to place this obsessive compulsive ritual elsewhere.

After I search for half an hour, I remember that, in order for you to have any sort of obituary or notice, someone in your family would’ve had to have written it. I turn off my computer and cry myself to sleep.

8

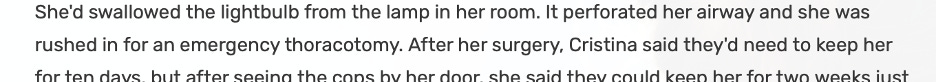

But it wasn’t enough. I needed another vision of you, something akin to how I would have remembered you, even I had to conjure it into being.

I went to DALL-E and bought a fistful of search credits, treating it like my own Ouija board. There’s nothing poetic about a search query, even if the giant AI neural tentacled whatever uses it to reassemble digital particles for my own bidding. There’s nothing poetic about imagining a new version of a dead person. There’s nothing poetic about seeing a machine reflecting you back to yourself.

The computer is a third order archive: electrified sand that I use to describe something like what I think you were over and over and over again, fifteen dollars at a time. My sorrow is a metallic drone warping with each bounce from the search walls.

DALL·E 2022-09-17 17.40.15 - Photograph of an unfriendly thinner older woman with a short blond perm, she is in Florida, her name is foxy

DALL·E 2022-09-17 17.42.27 - a 4’10” woman with a short curly blond perm named Foxy, she is wearing a bomber jacket

DALL·E 2022-09-17 17.43.06 - a 4’10” woman with a short curly blond perm named Foxy, she is wearing a bomber jacket

DALL·E 2022-09-17 17.48.48 - a 4’10” older thinner woman with a short curly blond perm named Foxy, she is wearing a bomber jacket, she is unfriendly

DALL·E 2022-09-17 18.00.00 - a 4’10” older thinner woman with a short curly blond perm named Foxy, she is wearing a bomber jacket, she is unfriendly

DALL·E 2022-09-17 18.01.01 - Photograph of an unfriendly thinner older woman with a short blond perm, she is in Florida, her name is foxy

DALL·E 2022-09-17 18.01.07 - Photograph of an unfriendly thinner older woman with a short blond perm, she is in Florida, her name is foxy

DALL·E 2022-09-17 18.01.16 - Photograph of an unfriendly thinner older woman with a short blond perm, she is in Florida, her name is foxy

DALL·E 2022-09-17 18.56.56 - you were my grandmother, your name was foxy, maybe you will be in my dreams, you were blond and unfriendly, you were my grandmother

9

The more I think about you, the less I have to make sense of anything.

10

You cannot after the fact after the fact. You can’t even after, let alone fact.

If God were a historian, he would’ve told Noah to at least consider the economic superstructure before the flood.

“The world you were born in no longer exists,” a Garfield and Friends meme reminds me while I revise this one more time.

11

When I see you again, as a howling deer, as a melting tub, in a shitty dream: Now please, please let me know something, anything. Please tell me your final name. Please tell me who said Foxy in your ears after they saw you dance. Tell me how you decided which children to give up and which to keep. Tell me how it felt when the children you left behind pulled a double con on you. Did they really keep your bed lined in pet pads towards the end because diapers were too much? Did you ever see me in your dreams? Would you have pulled a con for me? Is that how I got that prehistoric laptop in ninth grade? Did you know that’s where I’d write my first poems? Would you have ever read my poems, even if they were gay like your only son? Could I meet you there, could I dream of you in those ancient files? Are there any bones and ash or do I have to imagine your skeleton? Where can I leave this for you to read when you’re bored of walking around Florida? What should I call you to bring you near these words?

(All images in this piece except the final one were created using DALL-E, and many of the prompts written to generate these images were used as part of the piece itself. As seen in the piece itself, I wrote the prompts, the AI made the images, and I rewrote and rewrote the prompts to my liking. Not all results were shown here, but most were. It’s funny: I used to joke about starting a Simpsons Dark AI twitter, though I still just might, and now I’m making this. What hath God wrought.)

you’ve been flirting again

(heads up: this mixed media contains gay porn images and body fluids)

Well, that was a lot. Thanks so much. I really appreciate it. If you liked it, tell a friend. If you liked it a lot, buy me lunch or a drink or something. If you hated it, pretend I’m Iris Murdoch. —KJ